My

Story

Getting to Know Sophia Wong

I was born in Hong Kong as the youngest of two girls. My father is Chinese and my mother is Korean. At the age of 10, my family immigrated to Canada, and my older sister (Gloria) and I grew up in a neighbourhood full of trees and wildlife in North Vancouver. I completed most of my formal education at UBC, starting with a BSc in Honours Physiology and a minor in Music, followed by an MD, and subsequently a residency in medical biochemistry. After graduation, I spent a year and a half splitting my work week between Vancouver General Hospital, St. Paul’s Hospital, Abbotsford Regional Hospital, and Royal Columbian Hospital. It was a fantastic experience as I learned about the processes and operations of different clinical laboratories across the Lower Mainland. I now work full-time at Vancouver General Hospital as a medical biochemist, and also serve as the regional medical lead for pre- and post-analysis for Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) laboratories.

I was very fortunate to have been mentored by a number of incredible teachers throughout my schooling. Hoping to pay it forward, I regularly seek out opportunities to teach and engage with undergraduate students, medical students, and residents/fellows at UBC. I am the course coordinator for PATH 406 Clinical Chemistry in the BMLSc program, and the program director of the UBC medical biochemistry residency training program. Recently I have also developed an interest in patient safety and quality, and am completing additional training in these areas via VCH’s Physician-Led Quality Improvement Program and Harvard Medical School.

My partner, Leo, and I moved to Deep Cove in May. It has been wonderful to be back on the North Shore – we are grateful to be closer to family, and to be steps away from the water and wooded trails. We will also be welcoming a corgi puppy in the next few weeks, so we are super excited about that!

Less Known Facts About Yourself

JUST FOR FUN...

How would you describe yourself?

Solution-focused.What is the most important lesson in your career so far?

I am learning to work within the confines of our health care system, and remain hopeful that we can still have a meaningful impact.What is one major challenge that you’ve had to overcome in your career? How did you overcome it?

To speak up for what is right, even though I may be the youngest/most junior/only female/only minority in the room. There comes a point where doing the right thing matters more than my reputation or how I am perceived.What was the inspiration for your career route?

I became a physician because I wanted to be helpful to those around me. This is still how I approach most things in life: I enter conversations, meetings, relationships, etc. with the intention to help.What’s the most visited website on your Internet browser?

VCH Webmail, followed by Reddit.Your life would be meaningless without…

My family.Who’s one person you think everyone should be following on social media?

I always enjoy John Halamka’s tweets (@jhalamka).When are you the happiest?

I am happiest when Leo and I are in Japan. The people there are polite, thoughtful, hardworking, and creative, and I feel inspired every time I visit the country. The food is phenomenal and the scenery is breathtaking.Fill in the blank: If you really knew me, you'd know_____.

I am silly and have a sarcastic sense of humour.What’s something you wish you didn’t spend so much money on? What’s something you wish you spent more on?

Nothing! I am quite responsible when it comes to managing my finances. I am happy with the major purchases in my life.In 5 years time you hope to be…

A mother.So What's Next?

Retirement?

Conference in Vietnam (July 28, 2018)

Nutrition & Aging

Funding

News

Pediatric Cancer Initiative Recently Awarded

Dr. Poul Sorensen, a Professor in the UBC Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, was very recently awarded a US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant as the Vancouver Principal Investigator of a multi-institutional grant, led by Drs. John Maris of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Crystall Mackall of Stanford University. The grant award is $1.6M USD per year for 5 years. The grant is titled, “Discovery and Development of Optimal Immunotherapeutic Strategies for Childhood Cancers”, and is in response to NIH Funding Opportunity Number: RFA-CA-17-050 “Pediatric Immunotherapy Discovery and Development Network (PI-DDN) (U54)”, and is part of the NIH Moonshot program. The proposed Discovery and Development of Optimal Immunotherapeutic Strategies for Childhood Cancers Center is relevant to public health because these diseases remain the leading cause mortality in childhood and current standard approaches to treat pediatric cancers frequently induce unacceptable life-long morbidity. This proposal seeks to discover the fundamental mechanisms leading to high-risk childhood cancer phenotypes, including how these malignancies evolve to evade the immune system and resist modern therapies. The proposed research is highly relevant to the NIH mission as we will translate these discoveries into novel new immunotherapeutic strategies for children, adolescents and young adults with cancer, which are predicted to improve cure rates while diminishing the long-term toxicity experienced by survivors.

Funding

News Continued

UBC Pathology Researchers awarded four of seven CCS Impact Grants: immodestly stated - a dominant performance

The Department of Pathology Medicine at UBC has always been a strong contributor to cancer research. Members of our department such as Professors Phillip Clement, David Owen and Andy Churg have helped shape the practice of pathology through astute clinical observations tied to practice changing solutions for the pathology community.

Over the last 15 years great strength has arisen in basic and translational pathology research focussed on the cancer problem. British Columbia is now almost unique in the number of multidisciplinary cancer site-focussed research teams that have been developed and are effectively led by pathologists. Prominent examples being the lymphoma research team (Drs. Gascoyne and now Steidl), OVCARE (Drs Gilks and Huntsman, with Dr. Dianne Miller), breast cancer research teams (Aparicio; Nielsen) and the interdisciplinary pancreatic cancer research team (Dr. Schaeffer with Dr. Dan Renouf).

In 2018, of the seven grants awarded nationally, four were awarded to investigators from UBC’s Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine.

Focus

on

Recent

Faculty Promotions

Emeriti Recognition Ceremony

Newly promoted faculty members

- Dr. Andrew Weng, Professor

- Dr. Nickolas Myles, Clinical Professor

- Dr. Tony Ng, Clinical Associate Professor

- Dr. Wei Xiong, Clinical Associate Professor

- Dr. Hui-Min Yang, Clinical Associate Professor

- Dr. Ananta Gurung, Clinical Assistant Professor

- Dr. Miguel Imperial, Clinical Assistant Professor

Education &

Latest News

Education &

Research

Postdoctoral Life

What my entrepreneur dad taught me about surviving in academia

My dad came to Canada as a high school student in 1974 and went on to obtain an engineering degree and an MBA from the University of Toronto. In 1991, he started working in sales at a company in Eastern Ontario that manufactures wires and electrical cables. Six years later, he acquired the company through a management buyout with a partner and he has been managing operations there ever since.

When my dad took over the company in 1997, 60% of the business was dedicated to manufacturing flexible power cordage for use in appliance cordsets and extension cords. This was around the time that a lot of manufacturing was moving to China, particularly appliance manufacturing and the extension cord businesses, because these processes are labour intensive and it was (and still is) cheaper to perform the manufacturing overseas. Many electrical cable manufacturing companies supplying these sectors in Canada and the US did not survive this economic shift.

In those difficult times, my dad managed to sustain the company by doing one very important thing: becoming flexible and adaptable to different customer needs. Specifically, he shifted the focus of the business to developing cables for use in residential and commercial construction and also other industrial applications. These were end use markets that could not be moved overseas and suppliers, such as my dad’s company, could focus on becoming more efficient so as to ensure that their own products could still be produced cost effectively on home soil.

Survival of the adaptable

My dad’s experience of adapting to survive a volatile economy resonates with me strongly now that I am a postdoc. This is because the demands of “publish or perish” expose postdocs to many of the same stresses as leaders in business, and our survival similarly depends on us responding effectively when things don’t go according to plan. How do we as scientists manage uncertainty in order to circumvent failure? Answering this question for myself began with understanding how one of my dad’s favourite business mantras applies to academic life:

No plan survives contact with the enemy

As a postdoc, your job is to come in with a plan of what you want to do or adopt a problem that your supervisor is interested in. You might have a set of goals that you want to accomplish and have written down a timeline and list of tasks that you need to perform in order to meet those milestones. Perhaps you are already envisioning the completed manuscript in your head. It is also very possible that this project that you have built up and idolized will fail completely or lead nowhere.

Assuming that your project will succeed is as much of a fantasy as trying to figure out how much profit a company will make in two years. It is especially unsafe to bet everything in one direction because it is a low probability event that things will go according to plan. What you can do, and what I have observed my dad do in business, is always be prepared for the unexpected and be ready to respond to change in order to mitigate risk. In both business and academia, this might be achieved by diversifying your project portfolio (while still maintaining your core projects), not mindlessly focusing on a singular direction, grabbing onto new opportunities and keeping an open mind.

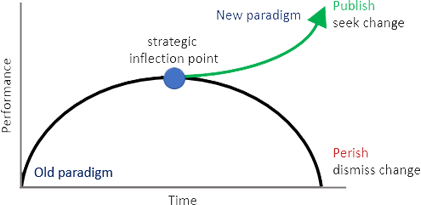

Constructing a research plan around a perceived unstable future is easier said than done. Key decisions about how to spend limited resources and what equipment to buy become more challenging because you are now factoring in risk/reward, the fact that competitors are getting better and the reality that demands are constantly shifting. However, maintaining this “paranoid” mentality (as Andrew Grove, CEO of Intel would call it), is ultimately beneficial because you are more likely to survive a strategic inflection point (Figure 1). The strategic inflection point is the point at which your usual way of doing things is about to stop working.

Figure 1. A strategic inflection point model for success in academia. Adapted from Andrew Grove’s book “Only the Paranoid Survive”.

Finding my entrepreneur instincts

Confronting an inflection point during my postdoc career was a potentially destabilizing event. However – thanks to the lessons from my entrepreneur dad – I was ready to re-invent myself when my research plan didn’t proceed as expected. I realized that continuing to progress in my career depended on me adopting a more flexible research strategy: one where I was not relying on a single research avenue to generate publications. I achieved this flexibility by dispensing my rigid long-term plan and diversifying my research portfolio to include new ideas and collaborations. There are risks and expenses associated with diversification, so I chose to branch out into related areas, where I knew I could leverage my strengths to produce results within a reasonable timeframe and at minimal added cost.

I have since acquired several new projects, each with their own risks and rewards, and this places me in an offensive position against unexpected events that might threaten my research career. Yet, I still subscribe to Grove’s advice of remaining paranoid by staying alert for new opportunities and studying my competitors. The moral here is that scientists can create advantages for themselves by embracing entrepreneur instincts. As in my dad’s story as well as my own, simply recognizing a need for change and then implementing it effectively can mean the difference between success and failure.

FACULTY AWARDS & HONORS

SINCE DECEMBER 2017

Dr. Bruce Vechere

2018 Distinguished Achievement Award (Recognizes meritorious performance)

Faculty of Medicine, UBC

Dr. Marianne Sadar

Awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Thompson Rivers University

Thompson Rivers University

Dr. Marcel Bally

Leadership in Canadian Pharmaceutical Sciences Award

Canadian Society for Pharmaceutical Sciences

Dr. Elizabeth Bryce

Patient Care Enhancement Award

Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists 2016/2017