Clinical management of adult primary brain cancer patients has evolved little in the past 30 years. Maximal safe surgical resection is followed by radio-chemotherapy. Surgery has become more precise with intraoperative image guidance technology including the incorporation of fluorescein or 5-ALA for enhanced tumour labelling. Compared to the glacial pace of therapeutic options, we have seen rapid advancements in our understanding of the molecular pathology of brain cancer and in the practical incorporation into daily diagnostic workflow. The World Health Organization has complemented and supplemented many of the traditional histological descriptive diagnoses with underlying genomic/epigenomic features that are much more relevant in the era of precision oncology. Even in the absence of targeted therapeutics, the molecular information often imparts crucial diagnostic and prognostic information that is relevant to the overall management of the patient (e.g. timing of treatment, use of concurrent radiotherapy).

Optimal treatment is reliant on the timely delivery of a suite of pathology data. This is particularly challenging in BC where patients often travel great distances to Vancouver for subspecialized neurosurgical care before returning home within a week, while waiting for the pathological diagnosis and treatment planning. Radio-chemotherapy might occur at a local cancer centre. The fundamental challenge, in the current era of precision neuro-oncology, is to provide a minimal molecular dataset that can impact care within a reasonable time frame. Prolonged turn-around-time not only negatively impacts clinical care, but also has significant deleterious effects on the psychosocial well-being of patients and their family.

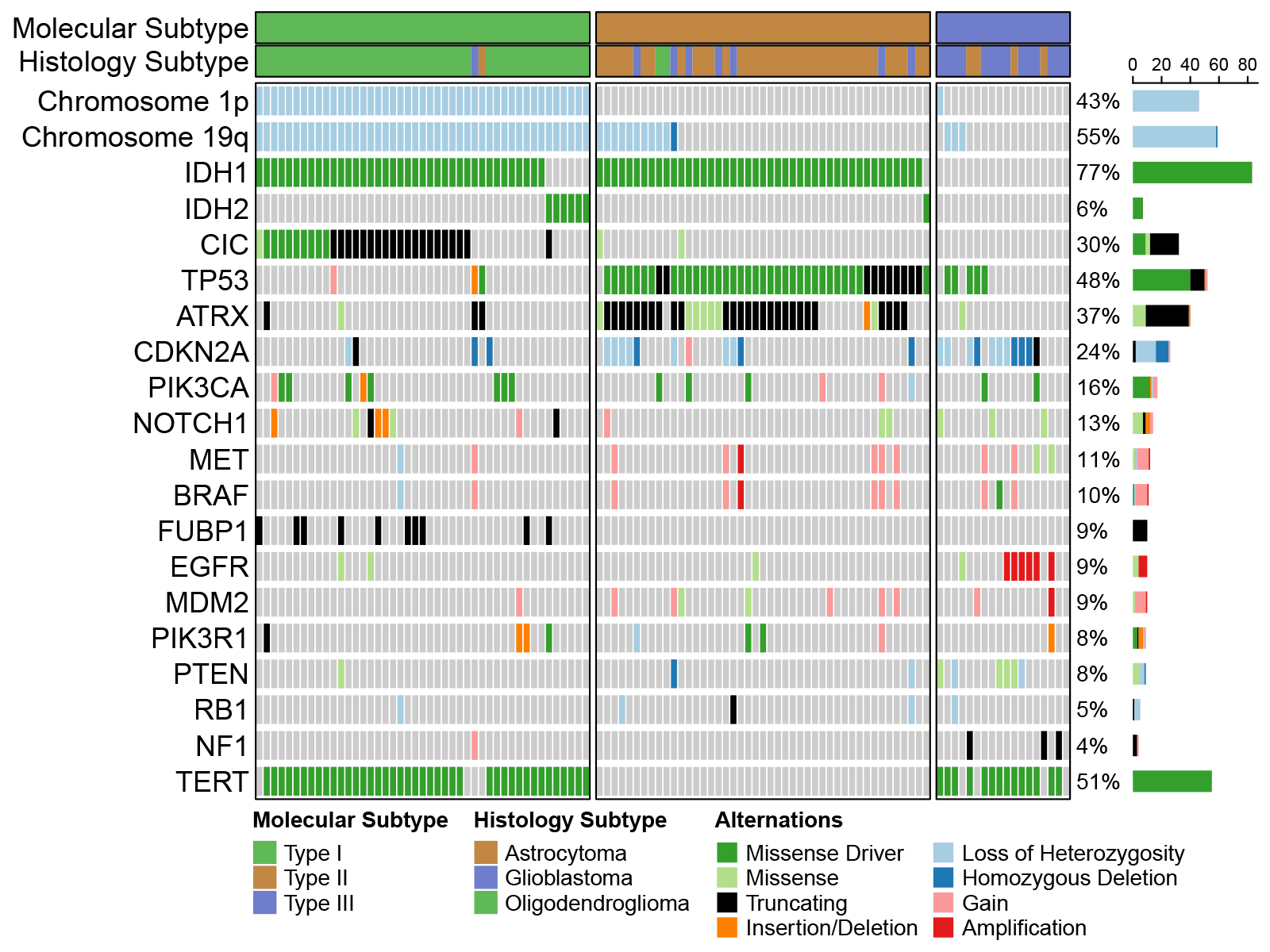

The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumours of the central nervous system, or CNS5, has codified essential molecular features that can inform on clinical performance of the three main types of adult infiltrating glioma (1). The current NGS panel (“Focus panel”) at BC Cancer represents a significant improvement over the previous test. However, there is still room for improvement, particularly in identifying copy number changes in key genes such as CDKN2A/B, EGFR, and PTEN (see Figure 1). We have recently developed such a glioma-specific panel and validated it on a large cohort of adult infiltrating glioma and additionally examined the impact of glioma copy number alterations on the FFPE proteomic landscape (2). This panel focuses on genomic alterations and will likely take 2 weeks to generate results. It still represents an improvement to the current diagnostic offering.

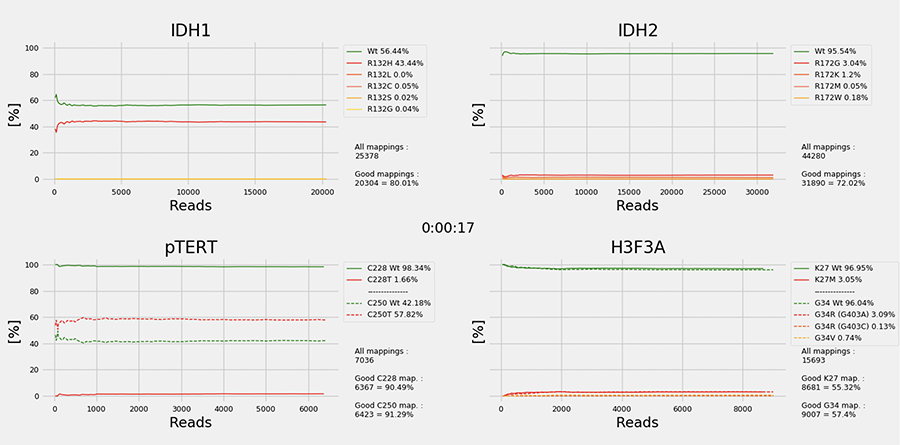

The brain tumour epigenomic landscape, in the form of intragenic and intergenic CpG methylation pattern, also has significant diagnostic value (3). The application of 850K methylation microarray technology has permitted the facile use of FFPE- derived DNA to generate epigenetic signatures that can inform on the unique diagnostic entity/subtype. Currently, the NIH organizes a weekly neuropathology methylation round attended by members of the clinical neuro-oncology community. This activity is essential to “reset one’s eyes” to unique and unifying epigenomic features. One example is the identification of high- grade astrocytoma with piloid features (HGAP), which displays overlapping and often confusing histomorphology, yet uniformly carries the same epigenomic signature. Accurate identification of HGAP is critical, especially in the era of precision neuro-oncology. The 850K methodology still takes time and suffers from “optimal batch penalty”, i.e. at least 1-2 weeks. We have recently embarked on a novel approach to generate diagnostically important methylation signature from brain tumour specimens within 2 hours, utilizing long read profiling of native, unmodified tumour DNA (4). We have also developed novel bioinformatic workflow and deep learning pipeline that represents an improvement over the random forest approach utilized in the original Capper paper (3). The incorporation of targeted DNA probes for key diagnostic alterations such as IDH1/2, BRAF, TERT mutations and copy number changes of EGFR, CDKN2A/B, and PTEN will significantly enhance the utility of this approach (see Figure 2).

The above approaches represent technological advancements that are essential in the implementation of a “value- based healthcare” initiative at VGH neurosurgery. This is part of a UBC Department of Surgery-wide project that assess patientcare workflow and identifies “choke points” and areas for improvement. Key stakeholders include neurosurgery, neuro-oncology, radiation oncology, and neuropathology are represented, and the first project is to improve the rapid delivery of molecular pathology data for glioblastoma patients - preferably within a week of surgery, and ideally before the patient is discharged. The driving motivation and the lessons learned from this project will be broadly transferrable to other brain tumours and cancers beyond the central nervous system.