David Hardwick, my friend and collaborator

I first met David, and his late brother, Walter (1932-2005), in the ’90s, when they discovered my theoretical work exploring ideas they had implemented more concretely. Their focus was practical implementation, having been been major movers in reforming Vancouver’s government along lines Jane Jacobs was later to describe. Their efforts succeeded, and Vancouver was long described as one of the world’s most livable cities.

My own research had been focused on further developing F. A. Hayek’s work, while the Hardwicks cast their intellectual net in different waters also dealing with complexity and self-organization. My growing involvement with them deepened my own work and opened avenues for taking it farther.

Although he studied medicine widely in many countries, David was a native of Vancouver, and always returned to the city he loved. As a faculty member of the University of British Columbia, David served as Head of the Department of Pathology and later as Associate Dean, Research and Planning in the Faculty of Medicine Dean's Office. In ‘retirement’ he became its Special Advisor on Planning. His influence there led to UBC becoming a leader in diverse fields of medical research not by top down planning but by empowering individual scientists who determine where they thought the most promising avenues of research lay.

Hardwick was a life-long member of the International Academy of Pathology serving in many capacities including President from 1992-1994 and Secretary from 2006 to 2015. David believed deeply that science should be based on what is called the gift economy rather than the market, and implemented his vision with the “Knowledge Hub for Pathology.” After every annual meeting of the US and Canadian Division of the IAP (USCAP), all research presented was made available world-wide at no cost. Confident as he was of the hubs’ merits, he was still amazed at how quickly it grew to become perhaps the world’s most important source of information in the field.

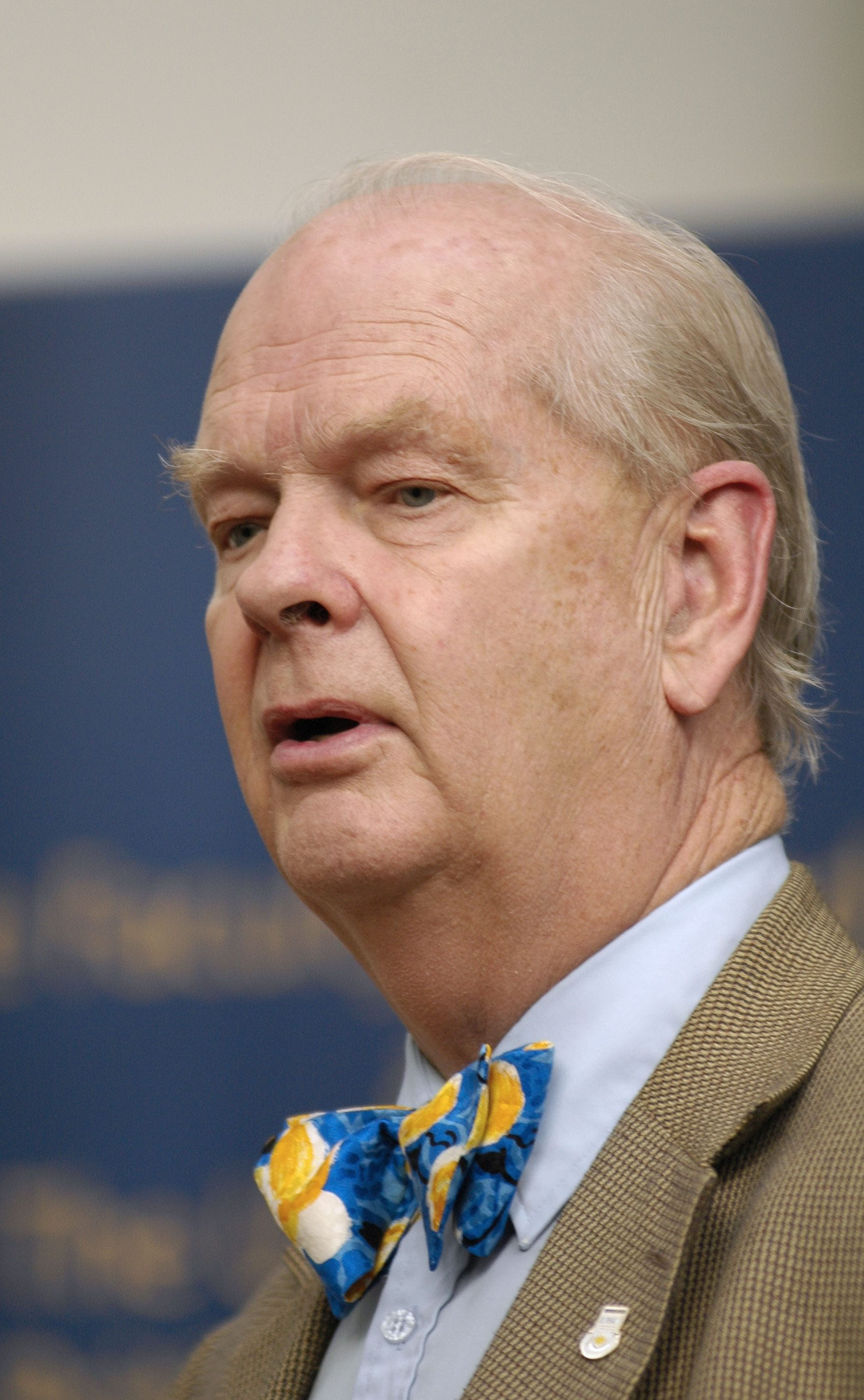

Those of us who knew him will always remember, and treasure, his offbeat sense of humor, from the ubiquitous home-made bow ties on various goofy themes, to his many puns and jokes, which in my experience always opened up his phone calls, no matter how important, to his offering a handshake, always moving it just far enough away to dodge mine, just before connecting. I was hardly alone. I will always remember David’s playing his banjo ukulele while all around sang wacky songs at a family gathering on Keats Island, off the BC coast.

In more serious contexts his playful side served an important tactical purpose. David had an intuitive sense of how large organizations worked to serve themselves over all else, and how they could be controlled. Appearing goofy to a bureaucrat encouraged the latter not to take David seriously, until he found he had been completely outmaneuvered.

For example, David mobilized alumni support to build the UBC’s Medical Student and Alumni Centre, which he supported in many other ways, such as cutting the grass, raking leaves and cleaning up. Such centers were often vulnerable to being taken over for ‘more important’ functions by university administrations and faculties. Hardwick ensured this would not happen to the MSAC by making sure the president of the Medical Undergraduate society for each graduating class sat on its board.

Around 2005 I began working with Richard Cornuelle, attending, and eventually helping organize conferences exploring the relationship of what is called emergent social phenomena with Hayekian concepts such as spontaneous order. Recognizing the compatibilities of David’s work with Dick’s focus, I arranged for him to be invited to one of our conferences in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. They got on well, and soon David was participating regularly and enriching the perspectives we discussed.

A journal, Studies in Emergent Order , grew out of these gatherings. When institutional and ideological politics over which we had no control led to its demise, David and some younger scholars created Cosmos and Taxis to carry on the original vision of a journal that put science ahead of ideology. It was harbored safely in Canada, at UBC, and is now 7 years old, with a solid record of refereed articles published in an online, open source, creative commons, format. The gift economy of science at work again. In David’s absence this would not have happened, but Cosmos and Taxis is now on a solid enough footing to last for several more years, at a minimum. In addition, David became involved with editing the Palgrave Studies in Classical Liberalism.

As David passes on to that ultimate mystery we all must someday enter, his work remains powerful and inspiring, while his memory for those of us who knew him remains treasured to us all.