Latest

News

Dr. Cheryl Wellington : Shifting research priorities to combat COVID-19: Title of project: COVID-19 inflammatory blood biomakers for clinical management, prognosis and evaluation of interventions

Dr. William Schreiber: Opinion A Model Career: role models can have a powerful influence on career choice – so we must strive to be good ones

Meet

Our New Faculty

Dept of Pathology welcomes new faculty Dr. Yongjin Park

A little bit about you:

I am a Bayesian statistician and data-driven scientist, focusing on developing new machine learning methods. I am excited to find a new pattern emerging from big biomedical data. But I become more excited if I can design and implement a machine learning algorithm that can make such scientific discoveries in a massive scale.

What would people be surprised to learn about you?

Perhaps, it is not about me and not surprising. It was when my research interest in deep learning methods was so high, trying to understand the mechanisms of Alzheimer's disease. I went to my daughter's daycare at MIT, and one teacher showed me a picture drawn by my daughter. It was a shape of brain coloured yellow/brown. I asked her teacher, "is it a human brain?" Then, she said, "Well, I asked students to draw his/her favourite body parts, and your daughter drew this and named its neural networks." I must have talked a lot about my research to my three-year-old daughter. Besides, my wife studies brain science.

What does a typical day look like for you and what are you currently working on?

I spend most of time looking at Emacs (a text editor) or shell screens, writing codes and analysis scripts of genomics data. These days I am developing a suite that enables us to analyze millions of single cell data efficiently to identify known and novel cell states.

What are you most looking forward to in your new role with BCCA/Dept of Pathology?

Although I am a bit introvert, I am most excited to meet new people, especially students and faculty, with whom I will work closely. I think of the discipline of pathology as a pursuit after causality, just like a detective would do for a criminal investigation. It demands the work of a multidisciplinary team. No one has a perfect clue, but we would collectively have a complete picture of causal mechanisms of cancer and other related diseases.

What did you learn as a researcher the hard way?

In computational biology research, finding a meaningful problem and defining the problem in a precise model is perhaps one of the most challenging tasks. When new trends of technology emerge, out of excitement, we tend to quickly adopt new technology to our problem without rationally thinking about its feasibility. I have made such a mistake a lot. I almost believe that it is better to design algorithms and implement tools in a problem-specific manner.

What do you like most about your job?

I am a little obsessed with details and visualization. To me, it often takes quite a time until I see the fruition of satisfying results and figures. Still, nothing is more satisfying than staring at these products. I also like the fact that researchers are constantly teaching each other regardless of positions. I enjoy learning new things from colleagues and students. It is never a one-way street.

What is the most challenging part of your job?

My job is to solve real-world biological problems using computational and statistical methods in the contexts of research and mentoring. I should be bridging between experts in two completely different fields. I need to convince a pure theoretician to work on a biology problem and teach quantitative backgrounds to biology-oriented researchers. Both are equally challenging.

What do you believe has been the greatest advancement for medicine in the last 50 years?

Human genome sequencing. With the help of sequencing technology, I believe we will see even more rapid advancement than ever seen before.

Going into the future, how do you believe medicine/science may change?

Medicine is an evidence-based science. As we collect more data, both actively and passively, it is not difficult to imagine that the very definition of many diseases will change. Therefore, the procedure and basis for diagnosis in many medical problems will be revised. We will be able to improve the accuracy of diagnosis by a collective and data-driven decision-making procedure, which involves multiple clinicians across the globe, including machine-learning algorithms. However, I do not share a view that Strong Artificial Intelligence can autonomously make more precise decisions than human clinicians. Humans are much better at reasoning causal relationships with only a few random examples.

What is the most helpful advice you’ve received?

I heard this from my postdoc advisor: Some computational problems are so easy to biologists and medical doctors. (Therefore, do not try to solve everything computationally)

What publications do you regularly read?

I follow great minds in machine learning and science through Google scholar.

What are some causes you care about?

I care about open creativity (if I understood the question correctly). I would like to keep on expressing creativity in research and attract more people to computational biology, thinking, "Well, I can do better than this guy!

How do you like to recharge?

I enjoy cooking although it does not mean that I am a good cook.

What are some words of wisdom or perhaps inspiration you wish to share with your colleagues?

Where is the finesse?

-Gordon Ramsey

Retirement

We wish you well and thank you for your contribution to the Dept of Pathology

Martin J. Trotter, BSc, MD, PhD, FRCPC

Dr. Martin Trotter was born in Ottawa, grew up in the Dunbar neighbourhood in Vancouver, and attended Lord Byng High School. He received most of his post-secondary education at the University of British Columbia. He obtained his BSc in Honours Physiology in 1981, his MD in 1985, and then did his rotating internship at St. Paul’s Hospital. He went on to complete his PhD in Experimental Pathology in 1990 at the BC Cancer Research Centre. Following his Anatomic Pathology Residency at UBC, Dr. Trotter received a McLaughlin Fellowship and trained in Dermatopathology for one year in London, U.K., at St. John's Institute of Dermatology under Dr. Neil Smith. Dr. Trotter is a Diplomate (Dermatopathology) of the Royal College of Pathologists (U.K.) and is a Fellow of the College of American Pathologists.

Patrick Doyle, MD

Dr. Patrick Doyle, a Clinical Professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, retired from the clinical practice of Medical Microbiology on March 31, 2019 after a 34 year career, and recently retired as Clinical Professor at UBC in January, 2020. Pat’s most recent work place has been the BCCDC Public Health Laboratory (PHL), where he is currently continuing as a part-time consultant on a team working to bring myehealth to BCCDC lab reports. Pat spent the largest portions of his work life, first at Metro-McNair Clinical Laboratories, and then at Vancouver General Hospital.Focus

on

Congratulations

to our newly promoted faculty members

Dr. David schaeffer (Nov 2019) VGH

Dr. Bing Wang (Kelowna General Hospital)

Dr. William Lockwood (Jul 2019) BCCA/BCCRC

Dr. Lik Hang Lee (St. Paul's Hospital)

Projects & Research Initiatives

transition into the future

news from VGH

The future of Immunology at VGH: Personalized Medicine in Immune and Inflammatory Diseases

News from

Centre for Blood Research, LSC

News

from BCCH

Next Generation Technologies for BC’s next generation: Expanding clinical diagnostic testing at BC Children’s Hospital

EDUCATION NEWS

Education

Latest News

Residency Program: some of the events that happened during the year...

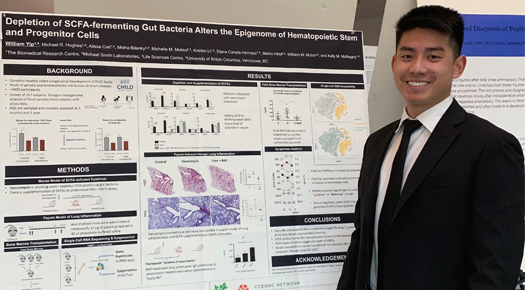

BMLSc student presents at Harvard National Collegiate Research Conference

News

Surrey Hospital

- As the second-largest city in British Columbia, Surrey is on pace to overtake Vancouver as the most populous city in the province by 2041.

- Clinic outpatient visits in Surrey are expected to increase from approximately 296,000 in 2016-17 to around 423,000 in 2026-27.

- Emergency room visits in Surrey are expected to increase from approximately 153,000 in 2016-17 to around 221,000 in 2026-27.

- Inpatient and outpatient surgeries in Surrey are expected to increase from approximately 47,000 in 2016-17 to around 63,000 in 2026-27.

Samuel H Krikler, MBChB FRCPC,

Regional Medical Director, Laboratory Services,

Regional Department Head, Laboratory Medicine and Pathology,

Fraser Health Authority,

Clinical Associate Professor, UBC

FACULTY AWARDS & HONORS

SINCE OCTOBER 2019

Dr. Ian Mackenzie

Clarivate Analytics Highly Cited Researcher 2019

Dr. Randy Gascoyne

Clarivate Analytics Highly Cited Researcher 2019

RESEARCH FUNDING & AWARDS

SINCE OCTOBER 2019

Dr. Bruce Verchere

Genetic Manipulation of hES-derived Insulin-producing Cells to Improve Graft Outcomes

Stem Cell Network

Dr. Mel Krajden

"Operating Grant: COVID-19 - Transmission dynamics/animal host/modeling"

CIHR Operating Grant

Dr. Natalie Prystajecky

Operating Grant: COVID-19 - Transmission dynamics/animal host/modeling

CIHR Operating Grant

Dr. Andrew Weng

Machine Learning for Flow Cytometry Clinical Data and Trial Analysis

CIHR Project Grant

Dr. Jay Kizhakkedathu

Novel hyperbranched polyglycerol-derived biliary excretable osmotic agents for peritoneal dialysis - preclinical evaluation

CIHR Project Grant

Dr. Philipp Lange

Tumour microenvironment mediated cell surface shedding creates unique targets and markers

CIHR Project Grant

Dr. William Lockwood

The effects of smoking marijuana on lung cancer development: implications for screening and early detection

CIHR Project Grant

Dr. Yang Decheng

Role of transcription factor NFAT5 in viral myocarditis: a novel strategy for therapy

CIHR Project Grant